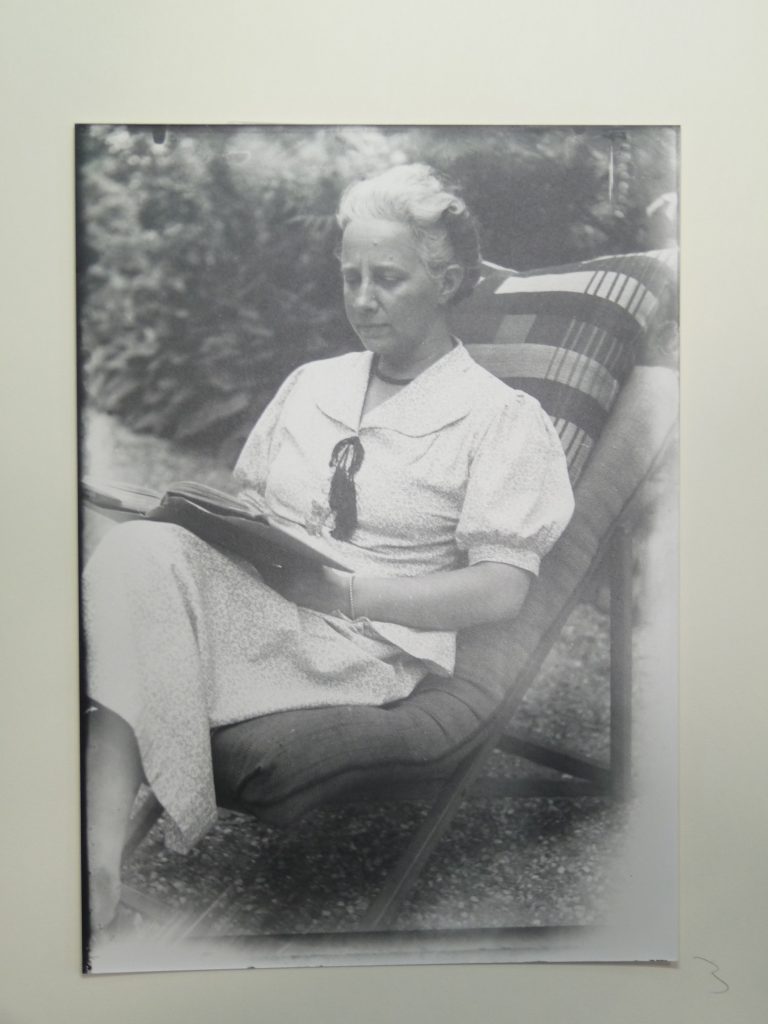

In the previous blog we read about Tera’s significance for science. In this blog I will look at Tera as a person.

Henny Coomans (1929-2010), her successor at the museum, speaks at her funeral. He talks about the decorations, tokens and honorary memberships that fell to her and says: Now that the soul has left the body, it is as if all those honors are no longer important and between all those decorations we see the person, the human being Tera van Benthem Jutting. She was a woman of great radiance, rich in spirit yet full of simplicity, highly intelligent but without envy, generous but without waste, ethically of a high standard, with a great zest for work and yet radiating tranquility.

Of course, the words spoken at a funeral are not decisive as a character description. You don’t speak ill about the dead.

The Labruyere children call her a sweet woman who came to their birthdays and brought Sinterklaas presents, a kind of surrogate grandmother. Her assistant Siebrecht van der Spoel also remembers her kindness and helpfulness. She didn’t run off with his results either, but encouraged him to publish himself. But she was certainly not sweet, thought van der Spoel, although small in stature she stood her ground. Several people call her reserved. She rarely showed her emotions. Even at Pico’s funeral, she did not shed a tear, according to Dick Dumon Tak. When Pico told funny anecdotes on literary evenings, tears could run down his cheeks from laughter, she only looked a bit amused. She rarely lost her calm , but could sometimes be unexpectedly witty and suddenly make a joke, as she once said about the Zeelanders: they are better off sailing and praying here than painting and writing poetry.

In her foreign correspondence, it is striking that she not only writes about the scientific subject of the letter, but always asks about the person as well. How are you and how is your wife. After her marriage, she invites as many foreign guests as possible to stay at De Wael, always hospitable. Her cooking is renowned. Dick Dumon Tak remembers that the food was always well prepared, but monotonous. At Christmas he was always served exactly the same menu.

There are two ways to get rich. One is making a lot of money, the other is spending little. The latter certainly applies to Tera. Tera and Pico have a healthy start in life, they come from wealthy families. Pico is certainly richer than Tera, but she is also “well to do”. Hard work is not done out of financial necessity, but out of intellectual drive and moral conviction. Although she regularly writes to her father from the Indies about her financial situation and later in the war sometimes complains about for example the price of vegetables, money is not a major motivation. She is hospitable, but also economical, paper is used twice, there is no heating if it is not strictly necessary, the wool of stockings is reused. That is partly because of the time she lives in, where waste is still seen as a sin.

Frugality as a virtue should not be confused with miserliness as a vice. She is certainly generous and she will always provide flowers or other gifts for friends or relatives on birthdays or other festivities.

She takes care of sick friends and cares about her cousins. But there are limits to her patience: After Wouter, Mientje now has study difficulties. She can’t get herself to start working, (..). Mien now expects a lot of good from a consultation with a psychiatrist, who, in my opinion, puts her off a bit. It’s also way too petty a case for a psychiatrist; Mien has to overcome this depression on her own. And you would say that someone who studies theology could find the necessary support in herself for that. I’ve invited her here for a few weeks now; we just need to talk. It’s strange that those two children get such shaky moods so late. I had already had them high and wide behind me at that age. (Mientje is twenty-four years old here).

She is, of course, like everyone else a child of her time. She dislikes informal conversation, has respect for breed and good manners, and dislikes ordinary speech and smacking. She is certainly somewhat snobbish but does not like boasting either. She thinks that people should know their place: Now there are (the hortulanuses) (..) The unfortunate thing is that these people (..) are very simple people by nature, standing right in between burgher boys and scientific people and for the first group too decent and not considered full by the latter. However, she has even more respect for knowledge and scholarship. She always speaks highly of Karel Boudijn, even though he is of “simple origin”.

She is certainly more free-spirited as a young woman than some other women of her generation. She thinks flying is fantastic, she doesn’t mind cutting into dead animals and she loves traveling by train and bicycle to the Riviera and Brittany with fellow students. She goes everywhere, to all meetings, and certainly has a substantive contribution there, but she is also expected to serve the tea, and she doesn’t make a big deal about that. Like all young people, she also participates in the fun, the student-like jokes and she is the shining center of the coffee table.

In the Indies she goes up on excursions alone or together with Betje Polak and a few koelies, she apparently walks like the best and has little understanding for people who cannot come along: With Marius I went to the Gedeh on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday and environment. (..). He is not a good climber at all, he was finished off the Gedeh excursion (an easy 7 hours). So that I hopped up and down the Pangerango on my own.

There are men in her life, but before she meets Pico it doesn’t seem like she feels a great need to get married. She adores children, enjoys playing with her niece and nephews, attending children’s birthday parties in the Dutch East Indies and helping children at the museum and elsewhere with their first steps as shell collectors. She never spoke about whether she would have liked to have children of her own. It is certain that with children it would have been impossible in her day to have the career she had.

The marriage with Pico is described by everyone as very good. When they are both old, they are considered a bit unworldly in the village. This, of course, often happens to old people, who still have habits and customs that have gone out of fashion with young people. It is recalled that they are always together and very introverted. She herself says that it is nice to be married to a man who “knows what you are talking about”. When Pico and Tera 1978 are interviewed, they say: the morning is for the garden, the afternoon for the household and the evening for science!

She never talks about politics. When she lives in Domburg, she does not get involved in the discussion about the Delta Works and keeping the Oosterschelde open. She also rarely talks about women’s emancipation. She doesn’t like sorority and boasting. For example, she says following the women’s congress in 1926 in Amsterdam: Hans W. tells the “wise women” what Dutch biological women do in her profession. She boasts a lot and I’m displayed 3 X life size on the canvas.

Like Pico, she never learns to drive a car, and although that may have been prompted by frugality, it appears that Pico is concerned about further industrialization and pollution and the disappearance of the nature he so loves. Then not having a car may be a political statement after all.

In addition to the snails and the shells, Tera has a great love for and knowledge of history and art history. She publishes biographies and writes about auctioning a Rembrandt. She likes going to exhibitions: I went to the historical exhibition with Atie. What a beautiful Rembrandts there were. And that great collection of Breitners. That almost speaks to you even more, because you feel your own environment in it. Before the war she likes to go to the cinema, Charlie Chaplin is a favorite, or to a concert or the revue. Pico is not, or much less, interested in such cultural activities, and so after the war they only go to lectures. She also stops listening to music for Pico. After his death, she watches concerts on television again in the Roggeveenhuis and listens to the radio again, which she then tells her niece Mien about.

Her life was for science, as Rinus de Bruijn writes after Tera’s death: While offering condolences in the auditorium, a resident from Domburg asked me whether I had also noticed that so many important people had stayed in Domburg. I searched my memory: of course painters like Toorop and Mondriaan, the writer Arthur van Schendel with wife and child for a short time, not to forget Rika Ghijsen and the Van der Feens. I could easily mention a few more names, but the point is that with the death of Tera van Benthem Jutting, I feel that an era has come to an end. A world of people whose lives were filled with science and art. Who made sure that many others benefited from their talents.

In the next blog we will tie up some last loose ends and look back on this project.