Last week we ended with “Weber has a little plan”. Tera writes on March 23, 1920: At an audience with Weber. Liked Thames molluscs very much, gave some new data. He has drawn up a nice plan confidentially, I’m interested.. Wants to have a lot of reptiles and salamandrines from Riviera. Oh professor I can keep them alive in my plant box. No, the intention is to conserve them, this is much more useful to us. Typical systematic.

Mollusks (Mollusca) are a phylum of invertebrates with a soft body and, as a rule, an external calcareous skeleton (shell). Mollusks come in a wide variety of shapes and are divided into different classes, the best known of which are the snails (Gastropoda), the bivalves (Bivalvia), such as mussels and oysters, and the squids (Cephalopoda).

In 1919 Tera had already become a member of the Mollusc Committee. The Mollusc Committee (or MC) was founded in 1915 by Wicher van der Sleen, among others. The most important task of the MC was to collect and record in a card system the (distribution) data concerning molluscs occurring in the Netherlands. This concerned marine species as well as land snails and freshwater and brackish water molluscs (quote: Corresp.-blad Ned. Malac. Ver.. No. 296 (May 1997)

On April 12, 1919, Tera writes in her diary: Made good progress with the shells of the committee.

Weber’s plan is twofold. He wants Tera to become a (student) assistant at the Zoological Museum and for her to work on Schepman’s mollusc collection, which he wants to purchase for the museum.

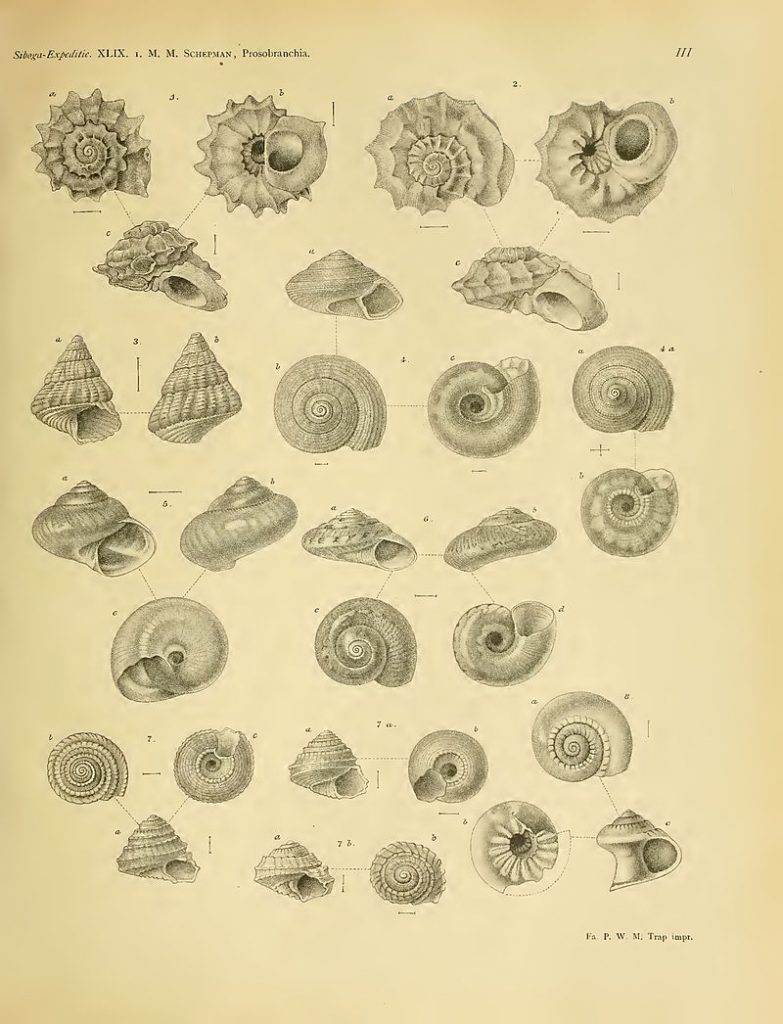

Mattheus Marinus Schepman(1847-1919) was a Dutch amateur malacologist and collector of land and freshwater molluscs. He lived most of his life in Rhoon where he is the steward of the Rhoon estate. In 1909 he moved to Villa Dennenhof in Bosch en Duin. Schepman is self-taught, but his knowledge is highly valued by many. Schepman is, among other things, closely involved in the zoological association and the mollusc committee. He buys, for instance, specimens of the inheritance Florentine Rethaan Macaré who we have encountered before. Moreover, after the Siboga expedition, Weber had asked Schepman to identify and describe the collected malacological specimens. In return, he was able to keep a few specimen . Between 1908 and 1913, Schepman published extensively on Gastropods (univalved snails) and described more than twenty-five hundred specimens. After Schepman’s death in 1919, his wife put the collection up for sale to the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden. However, the price for the more than eighty-five hundred specimens that the museum wanted to pay is considered too low and on June 10, 1920 the entire collection is auctioned in Utrecht, including two cabinets to store the specimens (source: Matheus Schepman a biography (van der Bijl, Molenbeek NMV, 2010).

Drawings of mollusks from the siboga expedition made by Schepman

Both plans work. On June 28, 1920, Tera writes in her diary that she and Weber and de Beaufort are going to pack shells in Bosch en Duin, the residence of the Schepman family. Weber paid more than six thousand guilders for the collection. The University of Amsterdam has helped out financially . And on September 15, 1920, her diary reads: Got hired by Weber!

Other students don’t understand what she finds so interesting to do at the Zoological Museum, and when asked about it, she jokingly says “dusting skeletons” because she thinks they won’t understand anyway.

The museum in 1920 has no electric light, no central heating and no telephone. The formation consists of one director, two assistants and one attendant. On her fortieth work anniversary, Tera recalls: The day I started working there was hardly anyone in the museum. No Professor Weber, no Miss de Rooij. The only one sitting in the boardroom working at the edge of the table was Dr. De Beaufort, then honorary curator. The whole long table in the director’s room was full of books, papers and bottles, but in a corner the size of a postage stamp Mr. De Beaufort was working.

Dr. Lieven De Beaufort (1879-1968) studied biology in Amsterdam. In 1903 he took part in an expedition to New Guinea and was subsequently awarded his doctorate in 1908 by Professor Weber. In 1920, he is Weber’s assistant at the zoological museum. He is married and has three children, Nella, Charlie and Hans. His wife died in 1922. Tera cares about the de Beaufort family. She knows the children, in later years she will sometimes stay there. When Tera later goes to the Indies, the Beaufort’s daughter, Nella, born in 1908, is also there. Tera shows her around

from left to right: Tera, Nelly de Rooij and Lieven de Beaufort. Man on the left unknown. Sitting down Max Weber

Weber and de Beaufort can be regarded as the most important teachers of Tera. The Beaufort is often kindly referred to as “Boss” or even “Little Boss” in Tera’s diaries. It is true that Weber is officially in charge, but since Weber is often in Eerbeek, de Beaufort is actually in charge of the day-to-day management of the museum. In her farewell speech, more than forty years later, she says: Professor de Beaufort has always been an example to me of a high-class person with a great sense of duty and an unquenchable love for his work.

Next time we will continue with even more plans.