In the previous blog we read how Tera and Pico got their new life on track as a scientific couple after the war. International contacts are also being strengthened again. Tera is certainly not resentful of other scientists, as she believes her German colleagues have also suffered under the National Socialist regime and the ties are simply being tightened again. She writes in June 1945: My German friends have fortunately left me alone all these years, as far as visits were concerned. I’m now longing to know how they fared.

Foreign contacts are becoming easier and more frequent. Train and air travel becomes faster and the international postal service benefit from this.

Guests from abroad who come to the Netherlands are received very friendly and if possible invited to stay for a few days on Walcheren in De Wael, otherwise in Amsterdam. The guestbook lists names from England, the United States and beyond. Famous malacologists such as Ruth D. Turner and Myra Keen stay on the Parnassusweg, but also the artist Marjory Howard known for the sculptures of mammoths who worked at the London Institute of Archaeology.

Erna Mohr from Germany writes in 1957: Hertzlichen dank für einige schöne und interesting Tagen mit Fossilen, Müsschlen und lieben Menschen .

Erna Mohr (here on a photo) (1894-1968) was a German zoologist from Hamburg. Even before the war she corresponded with Tera. During the war, the ladies kept in touch.

For example, Tera writes in 1943: A postcard from Erna M., who is in Schloss Waldenburg in Sachsen, with part of the bird collection of Hamburg. She writes: Vor 14 Tagen kam ich mit einer Fuhre Vogelbalg Schränke hierher. Das durfte in Zukunft das museum sein. Von desem selbst hörte ich bis her ebenso wenig wie von meinem Hause. Ersteres halte ich auch for aussichtslos, letzteres für nicht völlig ausgeschlossen. Ich mache mich zunächst ans Catalogizing der retteten Bestände. Not so nice for her. I can’t see myself sitting on the Mokerhei with boxes of beetles.

Tera had contacts in the Dutch East Indies and Singapore since she worked there in the nineteen thirties. After the war, contacts with the Indies become more difficult. Due to the Bersiap, the police actions and the Dutch acceptance of the independence of Indonesia in 1949, the relationship with the Indies has become more difficult. That means Tera has to rely more on specimens that are already in Europe, at the Zoological Museum itself, or at other museums. Even before the war, in 1935, she had received the collection of land shells for identification purposes from the director of the Raffles Museum in Singapore, Frederick Chasen (1896–1942). That was a logical choice even then, apparently her expertise was already internationally recognised. When the war breaks out, she had just finished, but publication had to wait until after the war, as contacts between Europe and Asia were interrupted during the war. As an expert on land snails from the Indonesian archipelago, specimens from those regions are of course always welcome, although she already has a lot of work to do. For example, she writes to M. Tweedie who asks for her help: “I am so behind-hand in my work, and this will remain so till my death. But if you cannot find a better and quicker occasion just send them along and I will see what I can do.”

Michael Tweedie (1907-1993) was an English biologist who worked at the Raffles Museum in Singapore. He explicitly needs Tera’s help identifying a particular group of Malayan snails. Their contact and way of cooperation over distance is described in an interesting article by Brendan Luyt. That article shows that Tweedie needs her more than she needs him. And that he does his very best to accommodate her in everything, in the hope that she does not drop out.

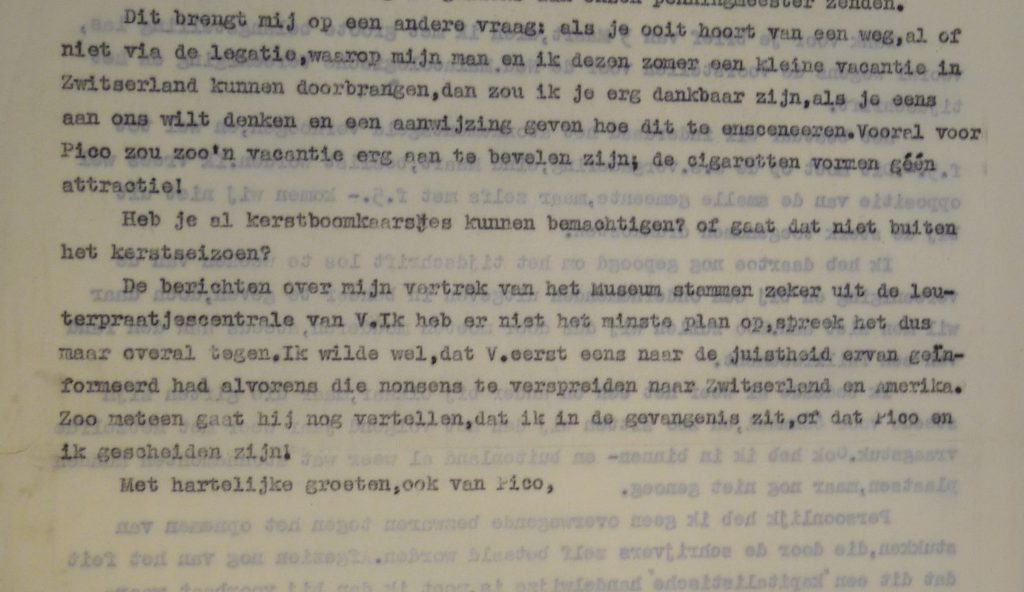

She also maintains a warm correspondence with younger malacologists. She corresponds extensively with Hans Kuiper and with Louis Butot. When Hans Kuiper is stationed in Basel in 1946, she asks him if he can manage to arrange a travel visa or something for her and Pico’s holiday to Switzerland. Whether that will work is not clear. Furthermore, there are apparently rumors that she would leave the museum, perhaps as a result of her marriage

At the end of her career, her address book contains two hundred and fifty seven contacts spread over forty countries. She had contacts from Brazil to New Zealand and from Norway to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and in almost all correspondence she writes of course about shells, but she always also kindly asked after the family. In addition to science, the person is always important. She corresponds in French, German, English and Dutch. She keeps copies of all letters sent and those copies are often typed on the back of, for example, advertisements, or concert programs, to save paper. The correspondence is saved in the Amsterdam City Archives, thousands of letters, from 1920 to 1990, eighteen large archive boxes full. In her farewell speech she says: Much depends on the cooperation of colleagues at home and abroad (…) I have always greatly promoted these contacts with other institutions, which usually yielded gains for both parties. As far as possible I have visited several museums myself, either to discuss problems or to work there myself. My best friends are in Leiden, Basel, Paris, Brussels, London, Frankfurt, Giessen, Copenhagen, Geneva, Stanford, Cambridge, Ann Arbor, Philadelphia, Chicago and Sidney, although I have never seen or spoken to some of them in person.

At some point I tried to calculate how much time Tera must have spent writing letters. The calculation was something along the lines of 15 minutes per notepad side handwritten. Only the correspondence with her father during the period that she is in the Indies amounts to at least 1 hour a week writing and 1 hour reading. I have stopped trying to calculate as I found the task quit impossible.

Was this blog about correspondence? In the next blog we will read about the foreign travels she makes together with Pico.