In the previous blog we read about Tera’s friendship with Maus. Old friends of Tera’s also come to visit when Wicher van der Sleen and wife, with whom she traveled through the Riviera in 1920, drop by. Apparently they are with a tour group, of which Tera doesn’t think very highly: I had the family Sleen visiting last week and walked with them and with their party select imbeciles through the botanic garden. How you get it into your brain to go on a trip with such an idiotic bunch of people is a mystery to me. The family Sleen move on to East Java, but come by again in August 1931 after they have said goodbye to their travel group. The friendship that Tera felt for the ten year older Wicher at the time has cooled down somewhat, she clearly doesn’t look up to him as much: Friday last, Sleen gave a lecture here, I went, although I didn’t feel like it. Furthermore, none of the biologists was there, I call that ‘clear’. I think he’s noticed it a little, but neither his buffoonery nor his immodesty make him loved. It is such a shame that he uses his abilities he undoubtedly possesses in such an unpleasant direction.

She is happy though that he is willing to take some luggage back for her. It is true that her return journey has not yet been completely planned, but it will nevertheless have to take place somewhere in the spring of 1932: When the Sleens return, they will probably take a chest with my books that I no longer need here. I now have those impossibly large boxes that Mijer made at the end of 1929 cut in half. (…) It’s very nice that he wants to do it, of course he has hardly any luggage and a lot of space unused. And if I travel via Calcutta next year, I will of course not receive free checked baggage directly from Java-Amsterdam, while it also seems rather exaggerated to take everything with me to Calcutta first and then to Holland. We will meet Wicher van der Sleen again later.

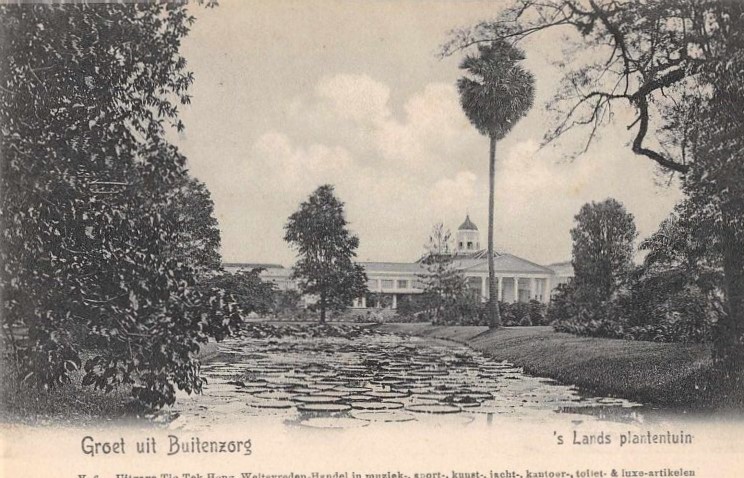

In 1929 there was a stock market crash on Wall Street, New York. The result is a long economic depression, first in the United States and then in Europe. In October 1931, the consequences of the economic malaise are also felt in Buitenzorg.

Tera now knows when she will return to the Netherlands, so she is not afraid of her own job, although she wonders if she will get her job back in Amsterdam. She does, however, decide not to go to India too, despite Prashad’s repeated insistence. She can pay for the trip to Calcutta, but because of the crisis she thinks it’s better to take the money to Holland. Moreover, she has received a letter from her sister-in-law Ans, in which she is advised not to stay away too long, because her father, now eighty-one, is apparently deteriorating. Finally, the political situation in India is far from stable. In 1930, Gandhi held his famous salt march and since then tensions between the British and the Indian population have continued to rise. Tera’s father strongly advises against it: as the situation in Br. India is getting more and more restless. This could create the danger that you may arrive at Calcutta, but only with difficulty could leave the country again, as this can only be done under the English flag.

She fears for Maus’s job for a moment, since he has no permanent appointment: Every day there are ukases about further cutbacks, and I fear that civil servants will also be fired before long. Then the botanical garden is always the first to be deemed as being “totally unnecessary”. And they are too stupid at the secretary’s office to understand how stupid that is! But later she also writes that Lieftinck is safe, because she herself is leaving and that Dammerman has now understood that he will not get a replacement for her.

As is often the case in times of economic cuts, the importance of science is underestimated. Tera is angry about this, but her anger and reproaches are mainly aimed at her bosses Docters van Leeuwen and Dammerman: This is much needed, because the botanical garden is not much respected and is in low regard, which is no wonder with bosses like Van Leeuwen and Dammerman. Van L. chatters too much, offends people by appearing quasi authoritarian and does little or nothing. Dammerman makes many enemies by his silence, and by always brushing people off or not answering letters at all. He doesn’t seem like a scientific hero to me either, and he doesn’t have the faintest idea of how a good museum should be run. I can tell you examples of that where you would doubt my truthfulness. Van Leeuwen and Dammerman always have more or less quarrels with each other, which does not benefit the blooming of the garden.

In the News of the day November 6th the article on the right appears: We inquired in the Zoological museum in Buitenzorg, where they monopolize the right to own scientific research. These scientific institutions keep complaining that they have too little staff, that new forces have to be added. And if a private individual wants to process some material — of course without this costing the country anything — then the director of that museum writes: “We have the right to reserve the processing of the museum material to the staff of the museum”. The budget of ‘s Lands Botanic Garden — of which the Zoological Museum forms the zoological half, as it were — with its large staff, in 1929 no less than 84 men, amounted to more than 5 tons. If we now remember that this is purely scientific work and that only a few investigations are carried out for practice and that the various institutes where applied botany or zoology is involved all have their own botanists and zoologists (such as, for example, the institute for plant diseases, which still employs half a dozen zoologists) and their own testing grounds (as culture and selection gardens), it is apparent that a lot of savings can be made here.

And as so often there are polemics in the newspaper (as illustrated above) about the importance of science in general and the Botanical Garden in particular: All the staff is in a state because of the more than scurrilous pieces that are written about the garden in the newspapers. (Kees) Van Steenis then drafted a plea in understandable indignation (in my opinion, not very cleverly written and even with some blunders). Which was later stripped down completely in a counter-article! But in such a proletarian way with the purport: there goes our expensive tax dollars. The general public will never, ever understand the importance of the garden, so it would have been better if van Steenis had kept quiet, because now he gets the very obvious reproach that he preaches for his own parish.

I think the ugliest thing of it all, however, is that Van Leeuwen, who at first had no objection to the publication of Kees’ article, now denies this and says that he has never approved it, because it harms the garden. All in all it’s not fun for Kees, he has a complete lack of human knowledge and a bad style, while I also always claim that he can never see the big picture, but everything is detail art. Again, Tera does not excel in diplomacy terms.

Kees van Steenis (1901-1986) is a botanist and has been working at the botanical garden since 1927. After the Second World War he will become professor of botany in Leiden, where the Van Steenis building still refers to him.

In the next blog we will read about Tera’s last days in the Indies and her return trip to the Netherlands.