The last weeks in the Indies are dominated by Tera’s departure, she has already send back a few book chests with the van der Sleen family. She packs up and the bike is taken apart again and boarded. She has booked a cabin on again, coincidentally, the Christiaan Huijgens. Due to the crisis, the boats are less full, and for the money of a second class cabin she can get a first class cabin, what a luxury, no cabin mate. The 5 boxes of books, the large suitcase and the bicycle box have already been taken on board, which gives a lot of space. The museum is empty and my house is empty, now all I have left is some rubbish at the Dammerman family. I’ve already stayed there for two days, because I couldn’t pack the pavilion at Pabaton and still live there at the same time. Now I don’t know any better then packing and unpacking suitcases is a normal, daily activity.

Just before Tera leaves for Holland again, she visits her brother in Surabaya. The days in Surabaya were very pleasant, I enjoyed it much more than last year. The Kostelijk family is very nice. We made a trip to the bird colony. The following Monday I was in Pasoeroean, Tuesday Marius and I did many errands in the city and in the afternoon I visited Nella van Boetzelaar (Nella de Beaufort now married to Baron van Boetzelaar) with husband and baby.

On Wednesday Marius and I went to Modjopahit to see the excavations of that ancient empire. Very interesting. It is not like the whole clump of temples (Mendoel, Pramambahan and Boroboedur) a remnant of worship, but of a real city with houses, altars, plates, statuettes, dishes, weapons, so real domestic things. (…) I am very glad I saw this.

The following Thursday I sat on the train for 13 hours and read 2 books. Maus came to pick me up in Weltevreden .

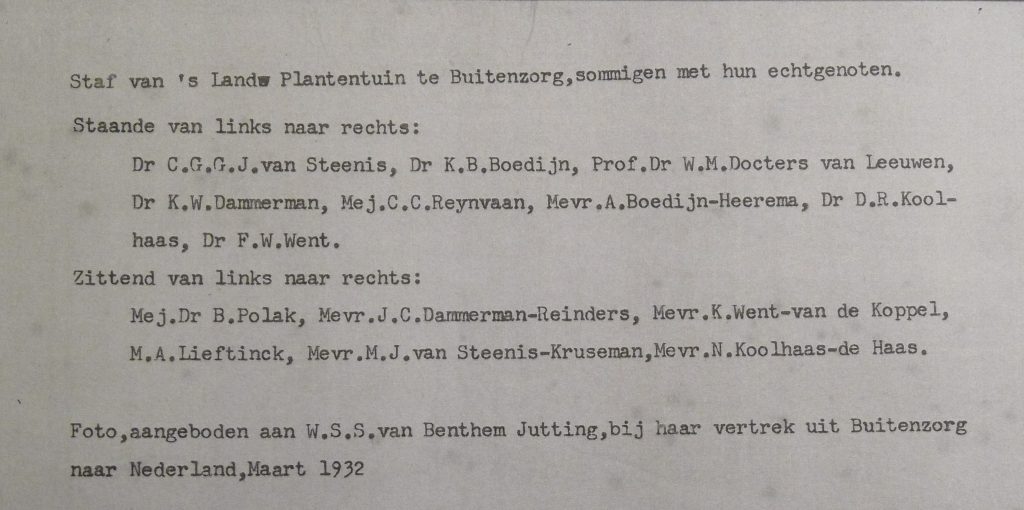

There will of course be a farewell party, with plays and a newspaper “de Blauwe Buitenzorger” instead of the “Groene Amsterdammer”. Here is the photo she receives with all her colleagues as a goodbye. Maus took the photo and was then “glued in” himself.

Maus accompanies her to Batavia and brings her on board, together with other colleagues on 15 March 1932. She writes in her diary: It is a shame to have to leave them. Maus with his squeezed white face is not happy either. And for a long time I see his long arm waving a large white handkerchief. The last thing I’ll remember about Java.

The return journey is not terribly exciting, there is an evening when the champagne is extra cheap and Tera drinks a glass or so too much, the next morning she has a headache. And there is some fuss and bickering among the passengers. The captain has sailed with her cousin Chris and pays extra attention to her, so she is invited to the Captains Table. Some others think that’s not well suited, a second-class passenger at the table with the captain, it leads to gossip and chatter. She just lets it happen. On April 1 they are in Port Said and on April 5 in Genoa, there is snow in the Alps. In Basel she takes the night train to Oberhausen and on April 6, 1932 at a quarter to ten she arrives at Holland Spoor in The Hague, where her father and her cousin Pico come to pick her up.

Her experiences in the Indies have changed her. As a woman she has grown and now goes her own way. As a scientist, from her Indies period, she definitively shifts her attention from saltwater snails to freshwater snails and land snails. From this moment on she will mainly focus on identifying and classifying freshwater snails and land snails from islands, especially islands in Southeast Asia.

When she retires 1964 she commemorates: This shift of knowledge from marine to non-marine molluscs is an interesting parallel with the development of knowledge of these animals over the course of history. The oldest writers on molluscs, from the Greeks up to the Middle Ages, dealt exclusively with marine molluscs. (…) It was not until around the middle of the last century (..) that attention was also focused on the terrestrial and freshwater molluscs. Thus, the course of events in general historical events is also reflected in that of the individual researcher. (..) Whether it was because both my parents came from an island kingdom and I was therefore homozygous predisposed for this, it is certain that in the last 25 years I have researched many island faunas, including those from Java, Sumatra, various Lesser Sunda Islands, North and South Moluccas, New Guinea, but also Curaçao, the Wadden Islands and the Zuiderzee Islands.

And so Tera is back in the Netherlands. For the past three months, blogs have arrived from the Dutch East Indies, where Tera resides from February 1930 to March 1932.

For me as a writer it was sometimes uncomfortable. I know the Indies from my mother’s tempo doeloe (the good old days) stories. The colors and scents of the Indies where it was a good life for the blandas (the white people). The rice table that we still eat, but that has very little to do with the real Indonesian cuisine. The accompanying film illustrates the colonial Dutch attitude towards “Our Indies” well.

A colonial time that we no longer look back on with undivided pleasure with the eyes of 2022. The exploitation of Indonesians, where Tera’s babu receives fl. 15,- per month, about € 300 today. Tera herself receives fl. 500,- per month, which is more than thirty times as much. This “brown” girlfriend probably has to support a family and lives in one of the undoubtedly shabby and poor kampongs. Tera is, like many people at the time, also guilty of explicit racism when she writes, for example: European patch shops are scarce here, there is a bad one with a half-black lady for whom everything is too much. She thinks it’s normal for the koelies to carry her luggage and she talks about the “annoying Mohammedan holidays”. Tera doesn’t like the “natives” much. When Thijsse writes a piece about his journey to the Indies, Tera makes blunt comment: Thijsse’s piece again does not argue in favor of his knowledge of the Indies. He argues that the natives know and love so many plants and animals. Now, every biologist knows that they call all trees Kajoe Api (= firewood) or tida tahoe (I don’t know), and are very cruel to horses, chickens and the like just to name a few examples. And then Thijsse refers to the representations of plants and animals on the Boroboedur, but forget that it was built by a completely different people, who did not provide the ancestors of the present Javanese.

I found myself tending to censor her letters, leaving out the overly rude statements. I might even have done some subconscious censoring, but the letters can be found on this site uncensored. I tried to tell the story through Tera’s eyes and Tera’s view of the then prevailing reality. I don’t want to justify that reality or that view.

In the next blog, Tera will find her way back in the Netherlands.