In the previous blog we saw Tera leaving the Dutch East Indies and returning to the Netherlands on April 6, 1932.

Even before Tera returns from the Indies, her father and she herself speculate where she will live. She could possibly move in with Nel Schoo, an unmarried cousin: I received a long epistle from Nel Schoo, much of which concerned our future home. She now seems to have been housed very much to her liking and suggested that I also move in with that family for the time being. That doesn’t suit me at all, for various reasons (..) I will write to her that I won’t consider it, but first want to settle in Haarlem and look from there. I have also roamed enough now and gradually want to settle down permanently without having to think about breaking up and moving again in a year. I also don’t know whether it would be so much fun living with her, she is so terribly shallow and not frugal at all. Well, this among us.

Father also wants her to live in Haarlem and is displeased if she would not stay with him first. Since he has maintained contacts with Tera’s friends in the Netherlands, he sees possibilities: Your wish to continue living in Haarlem for a few weeks or even months after your return will probably not go down well in Amsterdam, as people trust that you will now settle in Amsterdam. As rational as I think this is, I would of course be very happy to know you in my immediate vicinity again. It would be ideal if you could live under one roof with Nel Appeldoorn again, but she lives now with Mrs. Wiersma and she will probably not have enough space, as she also has an adult son at home. Of the other addresses you provided, the house of Mrs. Vorstman seem the best, better than that of Brandien (family of her mother), who no longer has a maid, only a working woman, who might keep you from work for the fun of it, because she has little idea has that a scientist is entitled to rest.

It is not clear where she initially ends up, she stays with her father and also with her sister-in-law Ans, after which she most probably rents again from a landlady in Haarlem. She starts her job again at the Zoological Museum where they certainly missed her.

Ans had already written to her that father Wouter was deteriorating, and after a short illness Wouter died on January 3, 1933, almost eighty-two years old.

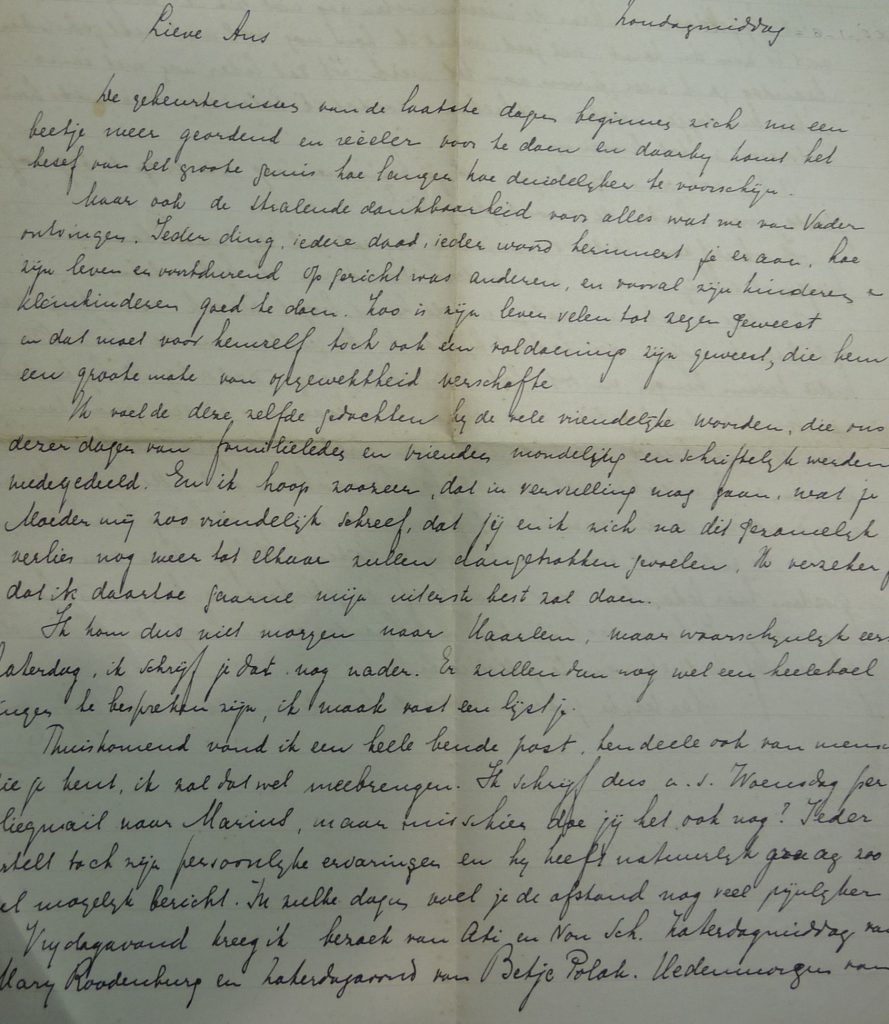

In a letter to her sister-in-law Ans, Tera writes: The events of the past few days are now beginning to appear a bit more orderly and real, and the realization of the great hole he left behind is becoming more and more apparent. But also the radiant gratitude for everything we received from father. Furthermore, it appears from the letter (printed opposite) that she considers the ties with her sister-in-law important.

Dealing with the estate is still quite a hassle. Marius is requested to give up his inheritance in favor of his children. After some deliberation, he agrees. Tera also changes her will and disinherits her brother in favor of her nephews Wouter and Christiaan and niece Mientje.

With the death of her father there is no longer any reason for Tera to live in Haarlem. His legacy also makes Tera a little more wealthy than she was before, and she decides to rent a house in Amsterdam at Parnassusweg no. 20. The Parnassusweg is located in the stadium quarter in Amsterdam South. After the 1928 Olympics, the stadium and surrounding buildings were demolished to allow for housing.

Above, Parnassusweg in the 1930s, with a view of the Olympiaplein. Tera’s flat must be located half way on the left. This spacious modern flat on the first floor was completed in 1932, in the style of the Amsterdam School. The flat has one sitting and dining room en suite, two bedrooms, a bathroom and a kitchen. There are two balconies, a bicycle shed downstairs, and, as the pinnacle of modernity, there is central heating. She will continue to live there until her retirement in 1964. She likes to listen to gramophone records, especially Beethoven, but also to the radio with recordings of concerts from the Concertgebouw. She receives guests, organizes dinners, she is a good cook. She continues to be a point of contact for her nephews and niece.

From the flat it is a good 5 kilometers by bike to her work on the Plantage Middenlaan. She will also continue to cycle there until 1964. The first work that Tera takes up after her return is writing a booklet about Dutch shells. She had already started that before she left.

In August 1925 Tera says in her diary: Weber (..) proposes whether I could write a book about Dutch shells. That would be all nice and good, but there are also all kinds of things against it. I’ll think it over in detail and then discuss it with him again later. At least it’s kind of him that he brings it up himself and claims that I have enough brainpower for it. But she can’t refuse Weber anything and she starts work full of good courage. She occasionally consults Weber about the manuscript, but complains in 1926: Talked to Weber about molluscs manuscripts. I think I can continue down this road. It just takes a long time. If I do one species a week is 50 a year, I need 6 years for the whole thing. Because many regions are still so poorly known, he would like to make another trip in September, for example to Limburg or Drenthe.

In his magazine Levende Natuur (32 (12) pp. 393-395), Jac. P. Thijsse in 1928: “A Fauna of the Netherlands is currently published at Sythoff’s Uitgeversmaatschappij in Leiden, edited by Dr. H. Boschma, (..) The work will consist of a large number of volumes, each devoted to a single group of animals, available separately and, of course, edited by scientists who have made their particular study of that group. The importance of such a publication can hardly be overestimated and we greet it with great satisfaction and with the stereotypical complaint: what a pity that this was not started much earlier.”

In order to get a complete overview of the Dutch fauna, Boschma started with this ‘Fauna of the Netherlands’ in 1927. Ultimately, this series will consist of sixteen volumes. The series is a valiant attempt to describe the entire fauna of the Netherlands, but it does not achieve that goal. The sixteen volumes together cover about five percent of the Dutch fauna, but include all molluscs, with the exception of the squid. (Source: Zoological diversity of the Netherlands, P. Koomen et al., National Museum of Natural History Leiden)

Tera’s mollusc book is not ready when she leaves for the Dutch East Indies in 1931. There she continues to work on the manuscript in between other work, and in 1933 Episode VII of the Fauna of the Netherlands is published: Mollusca (I). In the foreword Tera already writes: The literature on the Dutch Mollusk Fauna has been in a sad state for years”. She then mentions all the difficult efforts of her predecessors and concludes by thanking Weber: Thus the present work was started on his initiative and was completed with his constant friendly support. May it not disappoint his and all of your expectations!

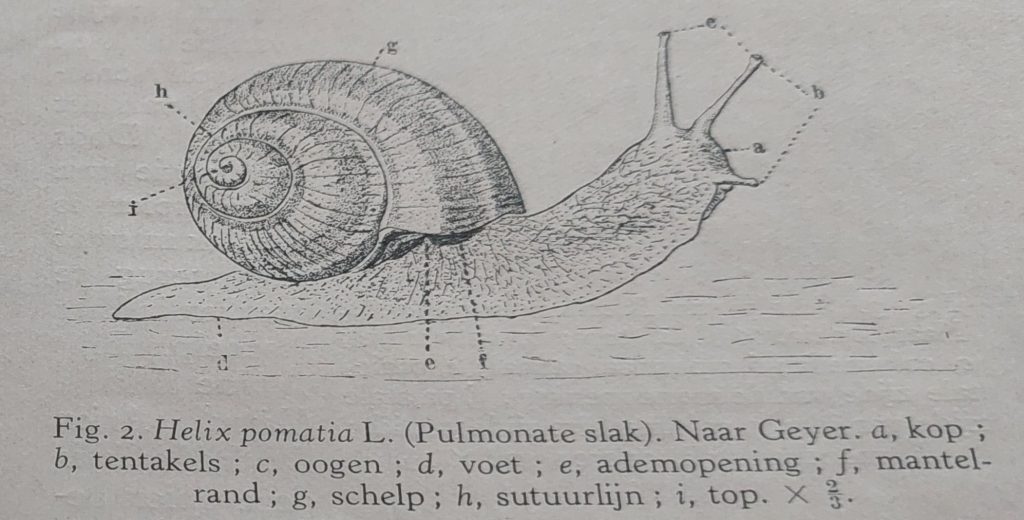

This is followed by a clear description of all known snails (Gastropoda) in the Netherlands with clear drawings (see fig 2., opposite), identification tables and locations.

According to current experts on molluscs in the Netherlands, it is still “the” standard work on Dutch molluscs and is still regularly quoted. A second volume follows in 1936, which she writes together with Hendrik Engel, and in 1943 another volume about bivalves follows: including oysters and mussels.

So now we saw how Tera said goodbye to the Indies and to her father. A new encounter in the next blog.