In the previous blog we saw how Tera’s Jewish friends fared and how Tera was involved. This blog is more about Tera’s own worries in wartime.

We already came across Lieven de Beaufort in previous blogs. De Beaufort is director of the Zoological Museum. His son, Hans de Beaufort (1915-1942) became a well-known motorcycle racer in the Netherlands before the war. At the beginning of the war, Hans became involved in the resistance. He is committed to helping allied pilots obtain false papers and to get them back to England via Switzerland. In February 1942 he tries to escape to Switzerland himself, but he is captured by the Germans near Besançon and imprisoned in Dijon. After an attempt to escape, he is sentenced to death by the Germans and executed. Tera writes: Yesterday de Beaufort received a very bad message about his youngest son, at the museum. He had been imprisoned in France since the beginning of March, while trying to get to Switzerland. Now the boy wrote a letter to announce that he has been sentenced to death by the court in Dijon. The letter was dated April 8, 1942, so the sentence has probably been carried out already. But of course you can never be sure, and maybe we won’t know for years. Poor Hans, he would rather have lived a little longer. And who knows how miserable those last days have been for him. No one who could help. And how was he buried? Presumably as a thug, an outcast, a rag.

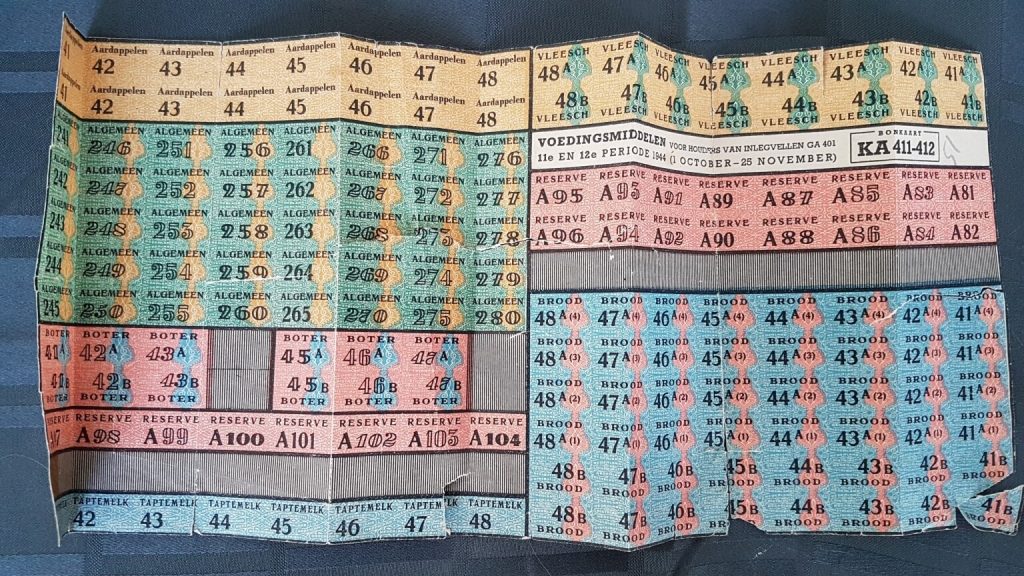

In 1943, the food supply begins to become more urgent. Almost everything is on food stamps and those stamps are mostly not sufficient .

Tera clearly also has a practical side and gives Pico advice from a distance about exchanging food stamps, arranging fruit and vegetables for the winter months. He still has contacts in Zeeland and can easily obtain products from the vegetable garden. She uses the museum’s cold stores to store food. Dear dear Pico, what a beauty of a cauliflower you have sent me! It came shortly before my departure to Nunspeet on friday. But to take it with me was much too difficult and unnecessary for me. So I put it in the museum cold store until Wednesday. That’s how I found it when I got back ice cold and snowy, but after defrosting it was excellent. Pico is not a smoker, but like all men het gets stamps for tobacco. Tera arranges a barter with tobacco stamps that can be exchanged for butter, sugar and other scarce products. She also gets chanterelles from Kitty every now and then: There were already a lot of chanterelles in the woods, of which I brought a large bag “Das Fleisch des armen Mannes” ( meat for the poor) . I make ragout mixed with cockle pie, very enjoyable.

Scraping food together is becoming an increasingly bigger job and when she can go to Nunspeet for a few days she says: It was indeed a great joy to be out for a few days and not have to worry about how to get all that you need the next day. The weather could have been a little better. Only Whitsun Day was sunny and quite warm. We then spent from half past ten to half past four in the sand drifts of Hulshorst.

A friend writes her a very dispirited letter and Tera complains about it: I wish I could do something about it. If I had a normal household, I’d be happy to take her in and make her comfortable to get through these dire times. But I’m far too busy to have guests and work,, especially now that everything is so much more difficult and – to give a small example – I had to walk 5 times, because of that crap ration of butter. That’s the way it is with everything. Currently, the vegetable supply is slightly better, but of course that will not remain the case. When I recently had someone to stay with me, I had a lot of trouble with the vegetables. Once I said to the greengrocer in the shop: you have to give me some more, because I am with 2 men. To which he said (in a crowded store): Well, miss, that’s quite something, first you have no man, and now suddenly two.

Transport is also becoming more difficult. From 1942, bicycles were confiscated during raids. Although ultimately only 1 in 50 bicycles is confiscated, Tera is still afraid of losing her bicycle and puts it safely away in her shed.

She wants to continu working at all cost and feels very responsible for the ins and outs of the museum. She therefore has to arrange other means of transport and she writes: I sincerely hope that you are still able to get around and that your bicycle is safe. Mine is untraceable. I now go partly by tram, partly on foot; 50 min. one way. Fortunately the weather has been beautiful all the time. Only if I have a lot of groceries, it is sometimes quite an effort. But since we haven’t received any potatoes in 14 days, at least I was spared that hassle .

And there is a lot going on at work too. Her colleague Engel is afraid of being arrested for the arbeitseinsatz and prefers to stay at home and de Beaufort also rarely shows his face. Tera writes bitterly about this: Engel I have not seen in days; he finds it easier to let someone else take care of business. Why can’t he come, and are all the other male staff always prompt? Sometimes they have to take back roads, and always have to be careful, but no one has ever been picked up.

I make a genuine effort to calm people down; so far it has always worked for me. One of the attendants recently said to me: “Miss, you are always so calm, we all rely on that”. I distract them with a joke or by assigning them extra short-term chores that interest them. Sometimes they’re just like kids. But I don’t think Beaufort’s eclipse politics is an example. “Oh,” Weber would say, “if someone hasn’t got it in him, it won’t come out”. You really get to know people these days.

In short, life in wartime for a single woman who does want to continue working is by no means easy, and her family members don’t make it any easier when she writes: After Wouter, Mientje now faces study difficulties. She doesn’t seem to be able to start working, and yet she doesn’t need the university right away, because she has to pass an ecclesiastical exam first. (Mientje studies theology) My opinion is that things are not going very smooth between her and her mother in Haarlem. My sister-in-law had hope that Mien would now help with the household at home. But, as is often the case, daughters of strongly overbearing mothers are not in the mood for that. Yet Mientje is also to blame, because she could very well lend a hand to a mother, who has done so much for her children. Mien now expects a lot of benefit from a consultation from a psychiatrist, who, in my opinion, is putting her off. It is also far too trivial for a psychiatrist; Mien must overcome this depression on her own. And you would say that someone who studies theology could find the necessary support in herself for this. I’ve invited her here so that we can talk. It’s crazy that these two children get such weird moods so late. I already had shaken those moods at that age.

So there is plenty to do and plenty to complain about. Next week we will meet a new friend of Tera’s.