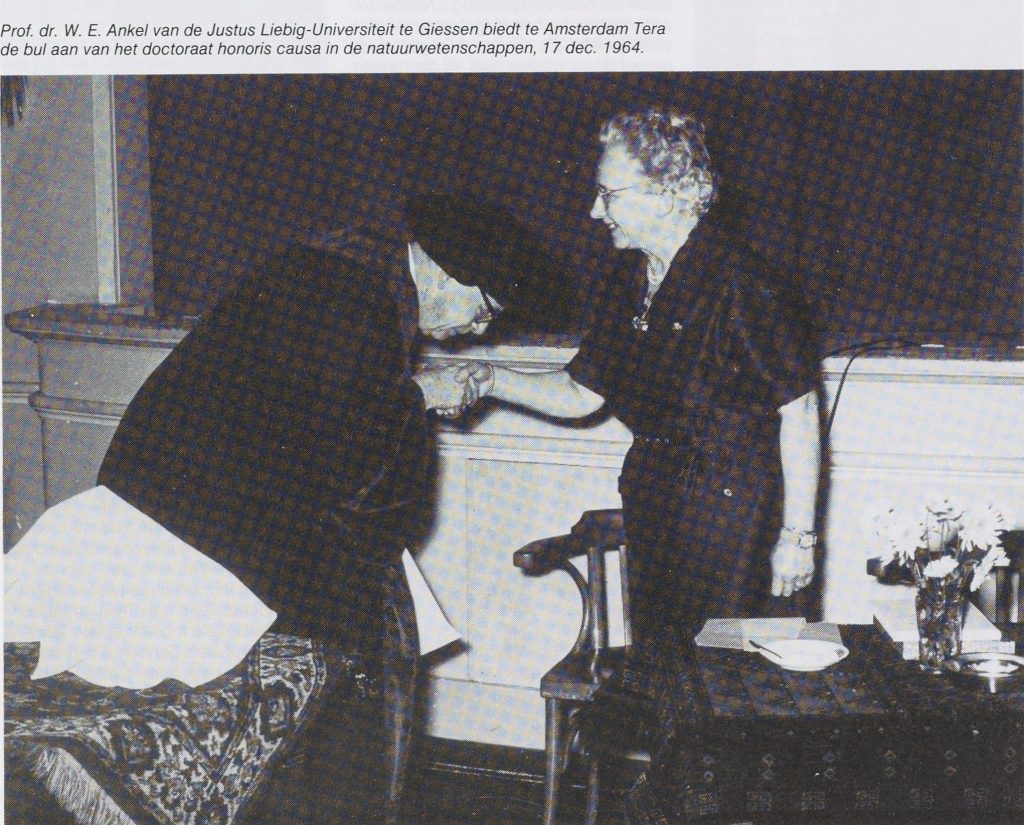

On February 6, 1964, Tera turns sixty-five and is allowed to retire. She waits till the end of that year to actually do so. Her colleagues Stok and Coomans and also her boss, Engel, are trying to obtain an honorary doctorate for her. First in Amsterdam itself, but the university board has the policy of issuing only one honorary doctorate each year and in 1964 it is not the turn of the Faculty of Natural Sciences. That means that other Dutch universities don’t want to honor her either, they don’t want any rivalry. Finally, Professor Ankel from the University of Giessen in Germany, whom Tera has known since the 1920s, arrives to bestow an honorary doctorate on her on behalf of his university. He makes an impassioned speech about the significance for humanity of biology and about freedom of mind. As a German, he refers to the Second World War when he says: Da predigen wir uns immer gegenseitig von der Verteidigung des Humanen und meinen damit die Forderung: homo homini homo. Und wir wissen doch aus der schmertzlichtsen Erfahrung, das das Humane, eben wegen seines hohen Freiheitsgrades, auch das andere in sich birgt: homo homini lupus! Und wir Biologen wissen obendrein, das wir dem Wolf mit diesem Vergleich sehr unrecht tun. (We preach homo homini homo, but we know from regrettable experience that the humane with its high degrees of freedom also contains something else Homo homini lupus. And we biologists know that we are doing the wolf a great injustice by saying that.)

Tera is delighted with this honorary doctorate. She feels like she is finally recognized as a scientist. The lack of a university title has always stung her. From that moment on she will sign all her correspondence, with the exception of Christmas cards, with Doctor van der Feen-van Benthem Jutting

In her farewell speech, she begins with a quip towards the alderman, who probably praised her modesty: In Zeeland we have a beautiful saying: you must not sit on rich man’s privy. In other words, you should remain humble. So I’ve never really stepped forward. I have done all this work quietly going about my business.

She then says: My interest in shells dates back to my primary school days, when my parents took the family from Nijmegen to some seaside resort during the summer holiday. On the beach I would collect shells and gradually became a bit at home with them. During my studies, this hobby expanded to scientific study, combined with visits to marine biological stations such as Den Helder, Helgoland, Port Erin, Wimereux, Villefranche, Monaco and perhaps a few others. It was not until much later that the land and freshwater mollusks were also involved. This shift of knowledge from marine to non-marine mollusks is an interesting parallel in the development of knowledge of these animals over the course of history. The oldest writers on mollusks from the Greeks up to the Middle Ages dealt exclusively with marine mollusks. The navigators, who made pioneering voyages to distant countries from the 15th century onwards, mainly brought sea shells with them, which is still evident from the many cabinets of curiosities in the 17th and 18th centuries. The great scientific expeditions, which sailed all the seas after the French Revolution, also returned home mainly with sea shells. Only around the middle of the last century, so quite late in the development sector of biology, attention also turned to land and freshwater mollusks, and this branch of our science was placed even more in the foreground. Thus, the course of events in general history is also reflected in that of the individual researcher.

So, as I said, having been lured from marine mollusks to land and freshwater mollusks, I have devoted myself within this branch, consciously or unconsciously, to the study of island faunas. Whether it was because both my parents came from an archipelago and I was therefore homozygous predisposed for this, it is certain that in the last 25 years I have researched many island faunas, including those of Java, Sumatra, various small Sunda Islands, North and South Moluccas, Misool and New Guinea, but also from Curaçao, the Wadden Islands and the Zuiderzee Islands. Furthermore, a number of limestone mountains in the Malay peninsula, which are so isolated in the plain that they are functionally comparable to islands in an ocean. I have even sometimes dealt with the islets of an island, so that is island study squared.

She then urges her successors to take good care of the collection. A typewriter or a microscope are replaceable, but the collection is the most valuable thing there is.

In her diary she writes: December 17: farewell celebrations in the main hall of Artis, 270 people present. Speeches by Engel, van Regteren Altena, Ankel, van der Spoel(…). Professor Ankel surprised me with a doctorate honoris causa in natural sciences on behalf of the University of Giessen. From the mutual friends I received a stereo microscope, from the museum officials the corresponding lighting. There is also a special edition from both Beaufortia and Basteria, as well as the honorary membership of the malacological association. Reception and festive luncheon. Ankel, Engel and wife come home for dinner in the evening. To Domburg until January 4.

That honorary membership of the Malacological Society was created especially for her on the occasion of her official retirement.

I now close a door behind me, but at the same time a new window opens with a view of what a French poet once called: “Le charme de la retraite”. With the memory of the friendship of all of you and with these beautiful gifts, I hope to be able to do some useful work in the next chapter. This is how Tera ends her farewell speech on December 17, 1964.

In the next blog we will see how Tera plans to spend her retirement years.