Tera’s fascination with snails, or rather shells, started early. She writes: My interest in shells dates back to my primary school days, when my parents went with the family to some seaside resort, Wijk aan Zee, Noordwijk aan Zee or Bergen during the summer holidays. I would collect shells on the beach and gradually became to know them a little. During her studies the fascination certainly grows, but initially it is not limited to shells. She also cuts Agoeti, a rodent from Suriname, noting: Heart, larynx and genitals preserved. Parasites in the liver and kidney. Beautiful orange teeth. Birds and insects also attract her attention. On a nightly walk she neatly keeps track of which birds she hears and sees and she writes in her diary: nightingale, grasshopper warbler, blackbird, song thrush, finch, chinchilla, lapwing, black-tailed godwit, curlew, oystercatcher, robin, coot and pigeons. It appears from her diaries that the flora is of less interest to her.

Collecting shells is of all times. Children and adults alike pick up shells and stones when they walk on the beach. That which is considered beautiful is preserved. When Columbus opens the sea in 1492 for larger voyages of discovery and the world is mapped more and more, collecting is increasingly elevated to an art form.

From the end of the 16th century, the movement that we now call the Enlightenment emerged. This movement is based on human reason. There is an emphasis on gathering and propagate all existing knowledge. In general, there has been a greater interest in science from that moment on.

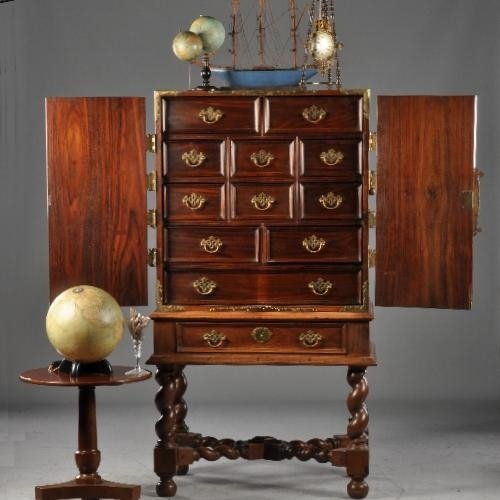

The rich start building collections in cabinets of curiosities or naturals cabinets. In the Netherlands, Bernardus Paludanus (1550-1633) is the first to be praised at home and abroad for his naturalist cabinet. When he was asked to come to Leiden, his naturalist cabinet must have already had a good reputation, because in his appointment the trustees expressly stipulated

‘with all his collected rarities, such as herbs, fruits, sprues, animals, creatures, minerals, earths, venins, rocks, marbles, corals, etc. and the others that he has to take his residence within this city. However, Paludanus does not go to Leiden, because his wife does not want to leave Enkhuizen. He becomes a doctor in Enkhuizen and people from all over Europe come to him to view his cabinet of curiosities.

Some collectors specialize by collecting only snails or shells or butterflies. In the anniversary publication, published in 1938 on the centenary of Artis, Tera writes: “Especially the wonderful products of the tropical seas, the shells with brilliant colors and infinite diversity of form attracted and appealed to the imagination. Amateur conchology grew and flourished and found enthusiasts among all classes. The new vogue spread rapidly and many private natural history collections which, at this time, were predominently conchological, were started.”

Another way of collecting and propagate knowledge is of course through books. In France, this led to an extensive project by Diderot and d’Alembert that will go down in history as “The Encyclopédie”. Scientific societies are also being created in many countries in which scientific knowledge is intended to serve to “better the people”. From the 18th century, this led to the establishment of museums, libraries, but also parks and zoos.

The curiosities and naturals cabinets are eventually transformed into museums. The oldest museum, the Ashmolian Museum in Oxford, opened in 1683, when Elias Ashmole donated his rarities to the University of Oxford with an explicit testamentary demand that the collection must be open to the public. Even women are welcome, a German visitor discovered as early as 1710. The Ashmolian is followed by the British Museum in London, from the start with a separate department for Natural History (1753) and the Louvre in Paris (1793). In the Netherlands, the Teylers museum in Haarlem from 1778 is the oldest, built in the house of Pieter Teyler, who bequeathed his collection and assets to the Teyler foundation for the promotion of art and science.

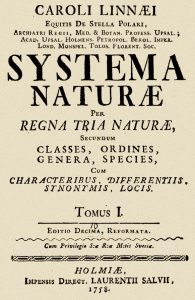

Carl Linneaus played an important role during the Enlightenment in Natural History, Tera’s field of study. As early as 1735 he laid the foundations of taxonomy by dividing nature into minerals, animals and plants. Linneaus is, as a doctor, admittedly more interested in botanics , but he also looks at the animal kingdom, being the first to classify humans as mammals. His Systema Naturae is regarded as the beginning of zoological nomenclature.

Such a system increases the interest in collecting and also initiates a scientific movement in which the entire natural reality, that is to say all animals and plants, must be described and named. The idea behind this is that one must first know and map the world before being able to say anything about function, reproduction and origin. Charles Darwin was also a great collector and his famous voyage on the Beagle to the Galapagos Islands was mainly intended for the collection of specimens. Most of his collection is now housed in the Natural History Museum in London.

As we have seen in Fred Dijsselbloem’s guest blog, after the publication of “On the Origin of Species” by Charles Darwin, the emphasis in biology is on phylogeny, the hereditary descent of groups of organisms. Hendrik Engel writes in his short biography about Tera: Between 1880 and 1914 University biologists in the Netherlands, and perhaps in the whole of Europe, shared a common ideal: to discover the phylogeny of all living beings. Tera’s University studies happened to fall in the beginning of another period of the history of biology: the splitting up of the science of life into the separate specialties of taxonomy, comparative physiology, functional anatomy, embryology, etc. The ideal of phylogeny still persisted but only as a vague fata morgana.

Tera herself ultimately opts for the taxonomy and will thus play an important role in the natural history museums of the Netherlands and beyond. But more on that a next time.