The previous blog was about the beginning of the war. Although “normal” life continues, the war soon becomes noticeable. Houses must be darkened and many evening gatherings are more difficult, because there is a curfew. That means that life for a single woman like Tera quickly becomes boring.

To get through the evenings and to emphasize their shared interest in history and biology, Pico and Tera write each other about work, about their scientific interests, and are getting excited about a starling pot (a nesting box for starlings).

The Algemeen Dagblad of September 6, 1940 reads: During the renovation of a site at Rokin 22, an old gable stone has come to light, depicting a jug or pot and two birds, with the caption “IN DE SPREVPOT”. This stone appears to have been hidden from the public eye during an earlier alteration of the facade, perhaps around the middle of the last century, so that its origin and meaning are no longer known.

At the beginning of 1940 another similar starling pot was found in Zeeland during archaeological excavations and this one is in Picos care. He either found it himself or as a voluntary curator he takes care of the collection of the Zeeuws museum and the said pot.

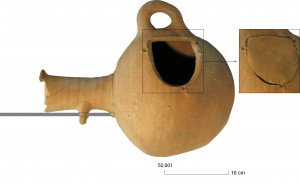

In April 1941 Tera writes to Pico: Now I also send you 2 photos, namely the front and back of a so-called starling pot, a 16th-century jug, dredged from the Leiden quay, of unglazed red earthenware. The ear is asymmetrical, along the neck are 2 loops (of earthenware) to put a stick through, and on one side is a hole (made intentionally, because cut in the wet clay). Our ancestors kept starlings in this “nest box”, as evidenced by a plaque in the so-called piggy bank alley, which should be called the starling pot alley. Whether the Dutch already harbored philanthropic tendencies towards birds at that time is left open. Quite possibly they ate them (hence the hole on the side facing the wall).

From that moment on it becomes a project. In the summer of 1941 Tera travels again to Domburg: In June or July I really want to come to Domburg again. If those traveling restrictions are still in place, can’t I come to you as a “maid”? If you don’t like my help, I’ll sleep with Rika, and you can summon me as often as you wish. My cooking skills have increased considerably since I no longer eat from the cook, because of the hassle with food stamps , I nowadays cook myself.

When she stays there, they discuss the starling pot project at length and both want to know all about starling pots, what they were used for, how they were made and how many there were. Tera would like to take a look at the Zeeland starling pot and asks Pico if he can arrange for it to be sent to her. In wartime, that takes a lot of effort.

Tera takes a scientific approach and makes a list of research questions: Found: where? When? By who? Age? Environment (other objects)? Owned by whom? What kind of baking: Turned? Glazed? Mixed with? What are the differences with Amsterdam starling pot? Sizes? Literature: already known articles and new ones (Prof. Swaen).

The Middelburg starling pot (see opposite) finally arrives at Tera in October 1942, brought by Felix Prince, a brother of Tera’s childhood friend Corrie Prince, whom we met earlier.

She makes drawings and photographs of the pot and asks the potter Wildenhain, whom she knows through her cousin Kitty, to examine it. On Pico’s advice, she goes to the library to look at old cookbooks: On your instructions, I requested 17th and 18th century cookbooks in K.B. (Koninklijke Bibliotheek) to look up starling pot dishes. I now have 9 on loan! It is priceless reading, and I wish I could send them to you, but they are too rare, and it has given me a lot of hazard to let the director of the library allow me to take them to the museum and I am not even allowed to take them home. Oosterbaan is properly afraid I’m going to practice with it in my kitchen. In the meantime I did indeed find a pie of young starlings, swallows and other small fowl in: “The trained and experienced kitchen master or the sensible cook, from 1701”. Besides, they ate all kinds of birds: thrushes, finches, sparrows, herons, moorhen, ortolan bunting, plovers, snipe, brent geese, hazel grouse, pheasant, gulls, teals, larks, lapwings, quail, duck, partridge, dove.

She goes to the picture gallery and finds images of starling pots, such as here in the painting by Avercamp: “Winter landscape with skaters” (opposite: fragment of that painting with starling pots).

Tera eventually writes a piece about the starling pot that is published in the Oudheidkundig Jaarboek in 1942 (Een Middelburgsche Spreeuwpot, Bulletin van de Oudheidkundige Bond 11jg (1942 pp. 88-90). The starling pot itself goes back to Middelburg and is now in the Zeeland museum.

The war comes very close to home when a number of professors are fired because they refuse to sign the Aryan declaration (a declaration that confirms that you are not Jewish), and some professors and other prominent people, such as mayors, are taken hostage, including Jan Verwey, who Tera knows from the Indies.

Artis is not spared either: At home I found a long letter from De Beaufort to inform me of the trouble in Artis. In the night from Sunday to Monday (July 1941), more than 300 incendiary bombs were strewn over there, as a result of which monkey house, reptile house, lion enclosures, elephant and giraffe stables and zoological laboratory all received minor fire damage, but hippo house, warehouses and the homes of 2 members of staff (a gardener and an attendant) completely or largely burned out. The attack appears to have been intended for an ammunition and supplies train, which was in the shunting yard of the wharehouse dock, but which had already departed 24 hours before. Thank God, otherwise the disaster would have been infinitely greater with the ammunition explosion.

In the next blog we will see how Pico is getting along in the war in Zeeland.