In the previous blog we saw Tera and Pico keeping themselves occupied with a starling pot. We now continue with Pico’s life in Domburg during the early years of the war.

Pico lives with his two parents in villa “de Wael” in Domburg. Pico is 48 at the outbreak of the second world war, his parents are old, his father is from 1852, his mother from 1858, only 6 years younger. Before the war, traveling is a good distraction for Pico. He travels to Utrecht or Amsterdam, but also to Switzerland. In addition, he has an extensive correspondence network that allows him to discuss all sort of things with like-minded people. Much of that is lost due to the war. That affects him and it makes him lonely. Tera understands that when she writes: I hope the task doesn’t get too much for you, the hassle in house with two infirm oldies, annoyance with staff, and lack of exchange of thoughts on the thousand topics that occupy your mind.

In April 1941, Pico’s father dies, Pico arranges the funeral and estate. Tera has flowers delivered through her family in Zeeland. Traveling to Zeeland is considered too dangerous. Tera writes: Thank you for the transcript of your speech. The thoughts are beautiful and the words are well chosen, so that others can also benefit from them. Your father himself would have been pleased too!

Pico has a difficult relationship with his overbearing mother, she is ill and probably bedridden. And sometimes it just gets too much for him. He doesn’t like to pour out his heart to Tera, or others, but somewhere a corner of the veil is lifted when Tera writes:

Dear dear Pico,

Thank you very much for your letter. It is very touching that you want to write all that to me and I already thought that you would have to give up more of your life again. I only wish you had confided your little secrets to me sooner. Now that I’m no longer a stranger to you, and your life is my life; and finally I have the illusion, that if you write down some of your worries in a letter, they will also be shifted a little away from your heart.

No one, including yourself, understands how to sustain this game of patience and unnatural living. Have you in a previous incarnation, or has one of your forefathers sinned so much, that you must now do penance? A strong maternal bond is a complicated case and can manifest itself in a thousand ways. But I’ve never seen anything like yours, and it’s a study in its own right.

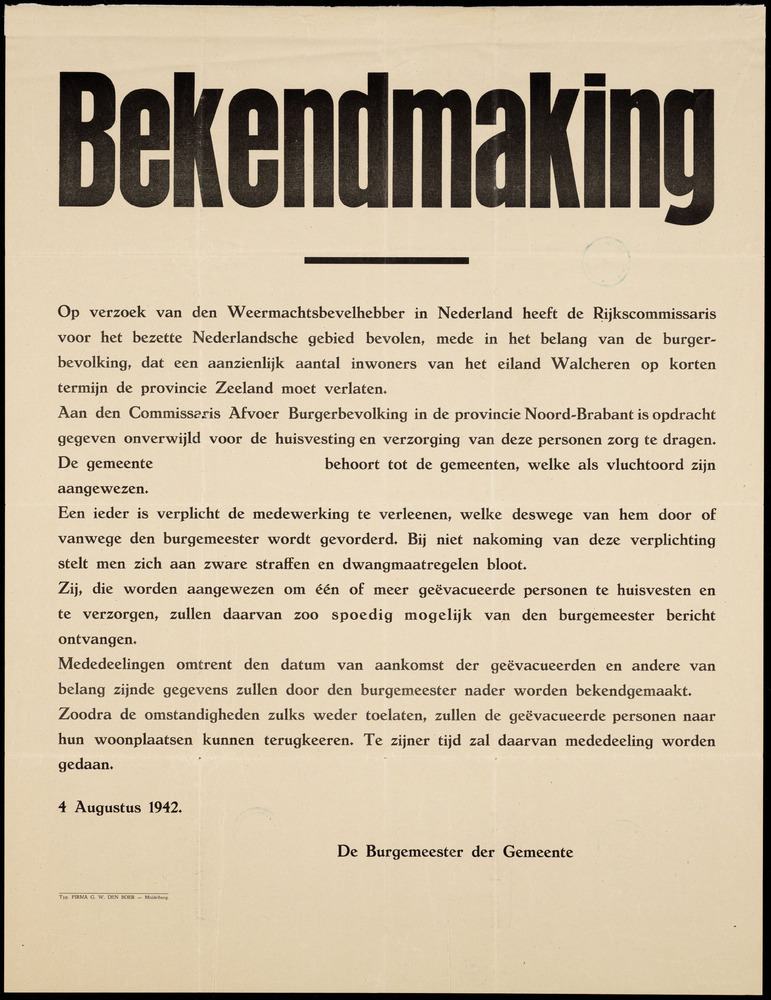

In August 1942, all residents of Walcheren (a Zeeland island) who don’t have jobs are evacuated to another province. (on the photo the official announcement). Zeeland is in the danger zone when it comes to war violence. The Germans confiscate Villa de Wael and Pico has to leave with his sick mother. Tera writes: Your letter to the museum was sent to me here. I thought it was a miserable message, and I now picture you: trotting and arranging and packing everything. How do you get those huge household effects together in 2 rooms, and how can you protect it from thieves and other misery. Have you already found a place to stay?

In Breda or the surrounding area you are of course more convenient situated to go up and down to Domburg. If you can still get there. What a shame and a pity about your vegetable garden, you don’t benefit much from it now. Whatever you can send to the museum, from household effects or vegetable garden, I will gladly receive and put away. There’s plenty of room, but we’ll have to wait and see if it’s safer there than anywhere else. In any case, it is better that you leave now than later in a stream of refugees, when there is no question of special care for your mother. I am very curious to hear what kind of lodging you will find. It will affect your mother deeply to leave this house with the thought that she may never return.

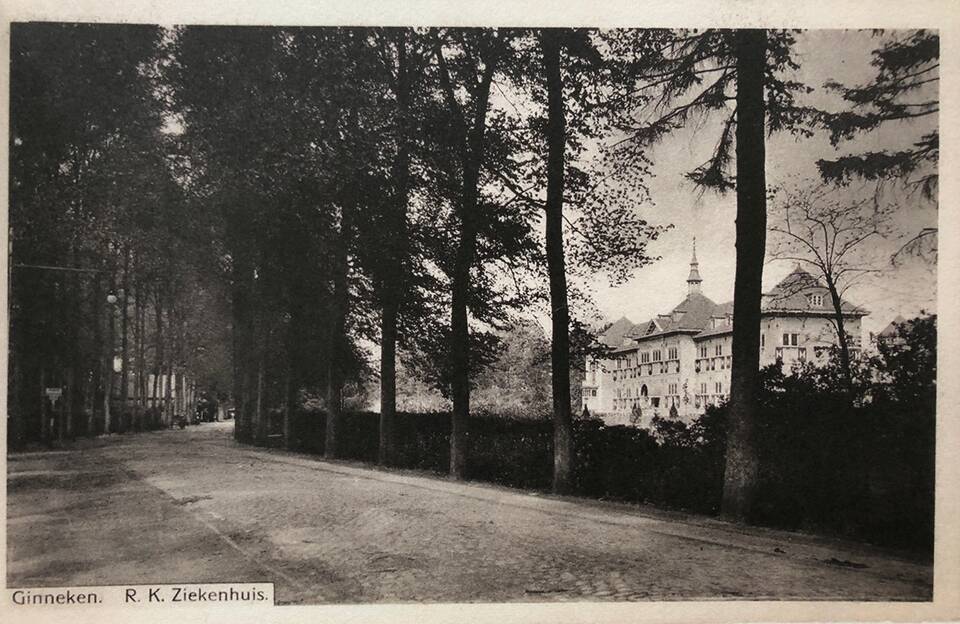

Pico finds shelter for his mother and himself in the St. Laurens care home (or asylum) in Ginneken (above in a photo from 1925) near Breda, where the nuns have a nursing ward. He sends many of his valuable books and belongings to Tera, who stores them clandestinely in the cellars of Artis. She stores photos, his tuxedo and extra clothes at home. In September 1942 she writes: You should not write to Beaufort for the time being, to thank him for storing your things, because …. He practically doesn’t know much about it.

Once Pico and his mother have settled in, Tera writes: From all your messages, for which many thanks, I understand only too well that the journey has been quite a tour de force for you and your mother, less for the journey itself than for all the emotions and effort, attached to it. I sincerely hope you now have the opportunity to breathe a little. It is already a relief to me that you no longer have to take care of the household. Do you ever go back to look at home and garden, or is that not allowed? What’s in your house now?

In Ginniken, Pico will “sit out” the war and take care of his mother. Next week we will say goodbye to Anna Weber.